Drug overdoses killed more people last year than guns or car accidents, according to the New York Times, but students at the University of Richmond have remained relatively unaffected by the current national opioid crisis.

First years and seniors alike said they had scarcely ever seen students taking opioids, but had found that obtaining drugs was easy on UR’s campus.

“Freshman girls can get whatever they want,” a first-year student from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, said. “But painkillers don’t have a strong presence on campus.”

A 2013 Counseling and Psychological Services campus survey found only 2.5 to 3.5 percent of students reported using an opiate not prescribed to them in the past 30 days. In the 2016-2017 school year, only 77 students saw counseling services for substance abuse of any kind, Peter LeViness, the director of CAPS, said.

“Opiate abuse is not one of our main concerns currently,” he said.

The opioid crisis started in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the medical world started taking pain more seriously, Rick Mayes, co-chair of the UR healthcare studies program, said. Pharmaceutical companies developed new painkillers that they pushed to physicians, claiming they weren't addictive, he said. But they are.

Although the government had done a better job of clamping down on doctors over-prescribing opiates in recent years, the issue persists, Mayes said.

One solution, proposed by leadership professor Jessica Flanigan, focuses on eliminating barriers to obtain prescription drugs, which she said violated people’s rights.

Flanigan, author of “Pharmaceutical Freedom: Why Patients Have a Right to Self-Medicate,” holds a libertarian view on drugs, including opiates.

“Why should your doctor have a right to make a bodily choice for you?” Flanigan said.

She criticized the government’s approach to the opioid crisis, asking what other public-health problem is treated with police and jails, desiring instead for a health-based approach and reduced stigmatization.

A senior fraternity member said marijuana remained the hardest drug regularly seen at parties, so he could understand why people tried painkillers. He said he was prescribed Percocet after a wisdom-teeth surgery and enjoyed the experience. “Percocet is freaking awesome!” he said.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Another student who wanted to remain anonymous said she had enjoyed taking Vicodin recreationally after her own tooth pain was gone, but she said she had researched the drug extensively beforehand. She wanted to know exactly what she was taking, she said, and even dissolved the pill in water to get rid of chemicals that would harm her liver.

Others had more negative encounters with opiates.

While abroad in Germany, a senior tried ketamine, a horse tranquilizer, and said she did not enjoy it.

“We crushed it up and snorted it with 100-euro bills,” she said. “I didn’t like it. It made me feel similar to being drunk, but a belligerent kind of drunk.”

Dylan Heaney, a senior member of a business fraternity at UR, said this type of drug use was not present at UR, however, “opioid use isn’t nonexistent on campus,” he said.

He said he thought the majority of drug users at UR were business-school students. Such students frequently traded Adderall, and by that logic, he said he could see harder drugs being traded just as easily, though he hadn’t witnessed it himself.

The first year from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, said she knew two different people who had overdosed on heroin while in high school. She did not have a positive view of tamer, more popular drugs such as lean, a mixture of prescription-strength cough syrup and soda.

“Lean is gross," she said. “Lean, like, fries your brain. It’s bad for you.”

Another first year from Pennsylvania also mentioned a big opioid problem in his hometown. College proved different though, he said, because he hadn’t seen anyone at UR drink lean at parties, let alone harder opiates. He had seen people on cocaine, though, and recalled another first year in Dennis Hall telling him he felt “coked out of his mind.”

Students seem to use attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications more often than opiates, Heaney said.

“I would expect more than half of UR students have tried someone else’s Adderall," a former sorority vice president said. “People snorted Adderall at parties to get it into their system more quickly."

There have not been any incident reports for opioids since 2006, Richmond College Dean Joe Boehman said, also noting that if students developed an addiction, they wouldn’t function at a level that they would need to at a school like UR.

UR added prescription drugs to the mandatory alcohol education and Wellness 85 classes in 2016, Steve Bisese, vice president for student development, said.

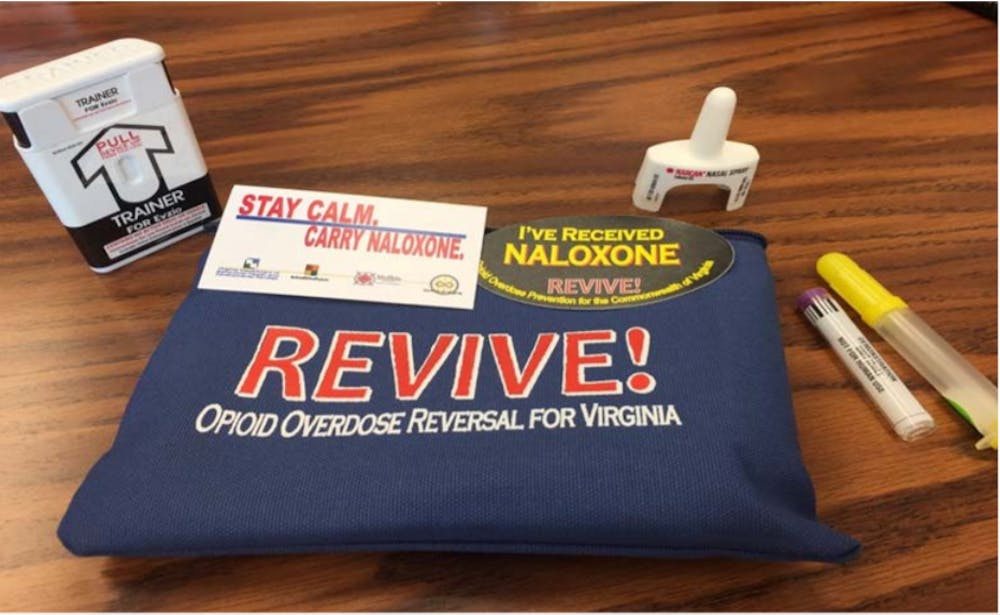

In addition, UR police carry NARCAN pens, a type of nasal spray that can help stop an overdose from becoming fatal, he said, adding that Richmond attempts to be preventative with its policies rather than punitive.

Contact writer Conner Evans at conner.evans@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now