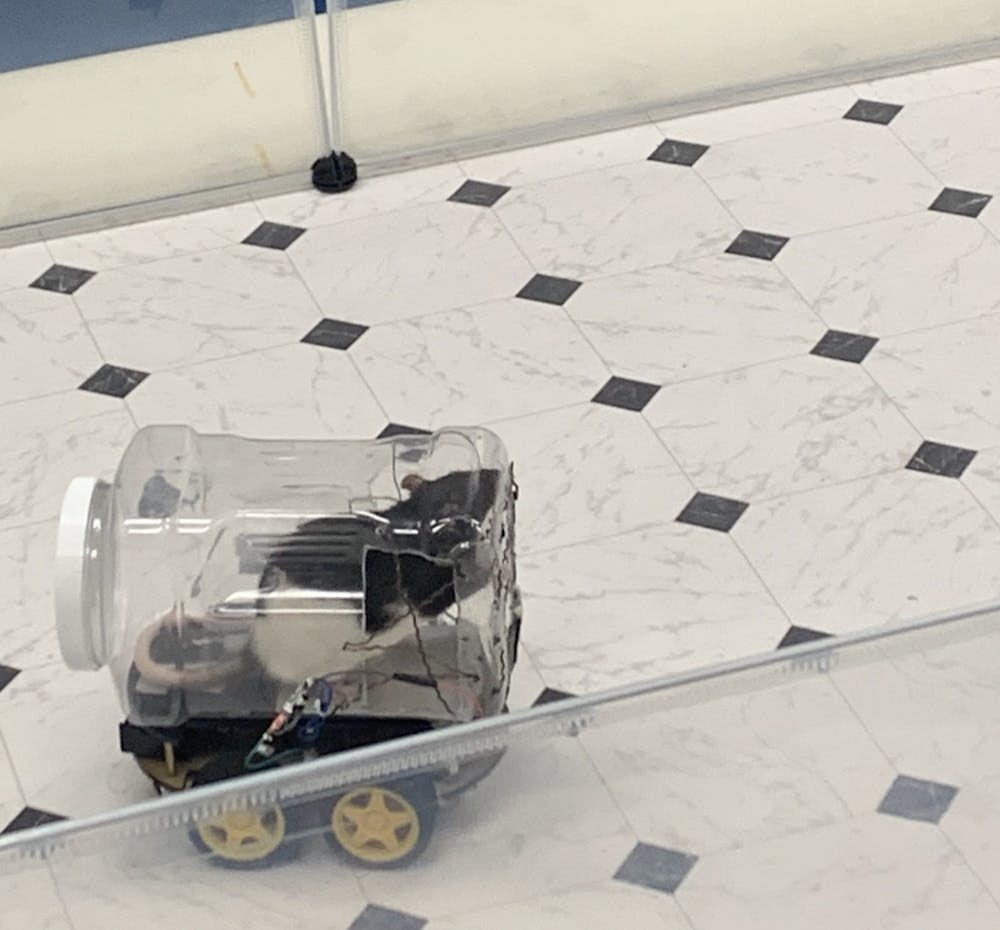

Researchers at the University of Richmond carefully placed two brown rats, Mario and Luigi, into tiny makeshift cars -- known as rat-operated vehicles, or ROVs -- fashioned out of clear plastic food containers, aluminum and copper wires. The team’s goal was to challenge the rats to operate the cars, which would move when the rat gripped a copper bar with its paws and stop when the rat released its grip. A sugary cereal prize awaited, contingent on their success.

To the team’s delight, a month of training not only determined that the rats could drive the cars forward, but could also make more complex movements, such as steering the ROV to the right or to the left.

Mario and Luigi’s success paved the way for a group of 11 male rats to drive ROVs as part of a psychological study that sought to examine how living in an enriched environment affected how animals performed complex tasks.

The idea to teach rats to drive cars came from Beth Crawford, a data scientist now working for Apple and former UR psychology professor. Crawford had seen a museum exhibit featuring an aquarium that would move depending on the direction that the fish inside the tank swam. Her sense of creativity compelled her to email Kelly Lambert, a neuroscientist and her colleague in UR's psychology department, and ask whether it would be possible for Lambert to teach a rat to drive a car.

Lambert’s initial reaction was to laugh and brush it off as a joke.

“Why would I want to do that?” Lambert said. “That’s not what we’re doing in the lab.” But as she thought more about the idea, she realized that teaching rats to drive a car could have a greater scientific application than she had originally believed.

“It’s an interesting, complex task about movement and travel,” Lambert said. “It’s about moving in time and space, but not moving the body.”

Lambert realized that training rats to drive cars could fit in with research she had been conducting on how a subject’s environment could affect its stress levels. With the help of Laura Knouse, another UR psychology professor and a clinical psychologist, Lambert and Crawford began brainstorming ideas for what the cars might look like and how the rats would learn to operate them.

Once Lambert, Crawford and Knouse had determined that the idea could work, they began to examine how it could fit into their current research. This included attempts to answer questions about whether rats that grew up in enriched environments would have an easier time operating the ROVs and how doing so would affect their stress hormones. To test the effects of an enriched environment, some of the eventual rat drivers were housed in cages with access to toys and other brain-stimulating objects. The others were housed in a standard caged living environment. The research team, led by Lambert, tested fecal samples of the drivers to determine their levels of stress while driving. The team published its study on Oct. 16, 2019.

The researchers concluded that the rats housed in an enriched environment learned to drive the ROVs more quickly, did so with greater interest and retained the driving knowledge much longer than their counterparts housed in standard cages did.

The degree to which the enriched environment rats outperformed those living in standard environments shocked Lambert. She said the finding could have a significant impact on how scientists understood the way environments impact human well-being.

“It’s something I talk about with my students,” she said. “Do we live in an enriched environment? If I sit here and stare at a screen all day, is that more or less enriched than the environment that my grandparents and my ancestors grew up in?”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

News outlets from the Washington Post to the BBC quickly fell in love with UR’s group of real-life Stuart Littles.

Lambert said she was attempting to keep up with the media demand in an effort to emphasize the scientific purpose behind her team’s study and the implications it could have for humans. Although Lambert herself has done about a dozen interviews so far, she said, UR had received around 350 media requests about the story just two weeks after its publication.

“I mean, what in the world?” Lambert exclaimed, shaking her head. As if on cue, the phone on her desk started to ring.

Most news stories on the research done by Lambert’s team have focused on the adorableness of automobile-driving rodents. The actual pioneers of the ROVs have largely avoided the spotlight.

The psychology department gets lab rats like Mario and Luigi from a Western Virginia-based branch of Envigo, a global contract research corporation. Lambert emphasized that all of the department’s rats are treated humanely and that the methods used by her team had been approved by UR’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

All of the driving rats spent the first three and a half weeks of their lives at an Envigo facility before arriving at UR and being separated into enriched or standard cages. Although the rats used in the study began their driving training about five months after their birth, the pilot program that Mario and Luigi participated in began when both rats were a little over two months old. Because Mario and Luigi did not participate in the study, they were housed in standard cages for the duration of the test program.

As the first drivers of their species, Mario and Luigi had the distinct honor of receiving names, a practice that Lambert said did not occur for the other rats. When necessary, the team identified individual rats in the study trials by the color of their tails.

Nate Fox, a 2018 UR graduate, co-authored the study as part of Lambert’s team, as did several other former UR students. Fox also named and trained Mario and Luigi. The trio (Fox, Mario and Luigi) had set out to try to accomplish what no rat or scientist had done before.

“[Fox] was the first to say, ‘Sure, I’ll try to teach a rat to drive a car,’” Lambert said, laughing. “There’s no protocol for this. We were kind of training each other -- the rats training us, us training the rats.”

The pilot trials lasted about a month, as Mario and Luigi learned to drive the ROVs in 15-minute sessions that occurred at least four times a week in a learning process roughly half the length received by the rats in the actual study. In the study, the rats learned to drive over a period of two months, receiving five-minute training sessions three times a week.

The initial training and the enriched environment study rewarded successful drivers with Fruit Loops. In later trials following the study’s completion, Lambert’s team attempted to see how the rats would respond to the driving task without a reward.

The team continues to run “maintenance trials” with both male and female rats as a way of keeping the driving task fresh in their minds.

As UR and the media rightfully celebrate Lambert, Fox and the rest of their team, it also seems fitting to celebrate the unsung heroes who helped make it possible: Mario and Luigi.

Contact opinions editor Riley Blake at riley.blake@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now