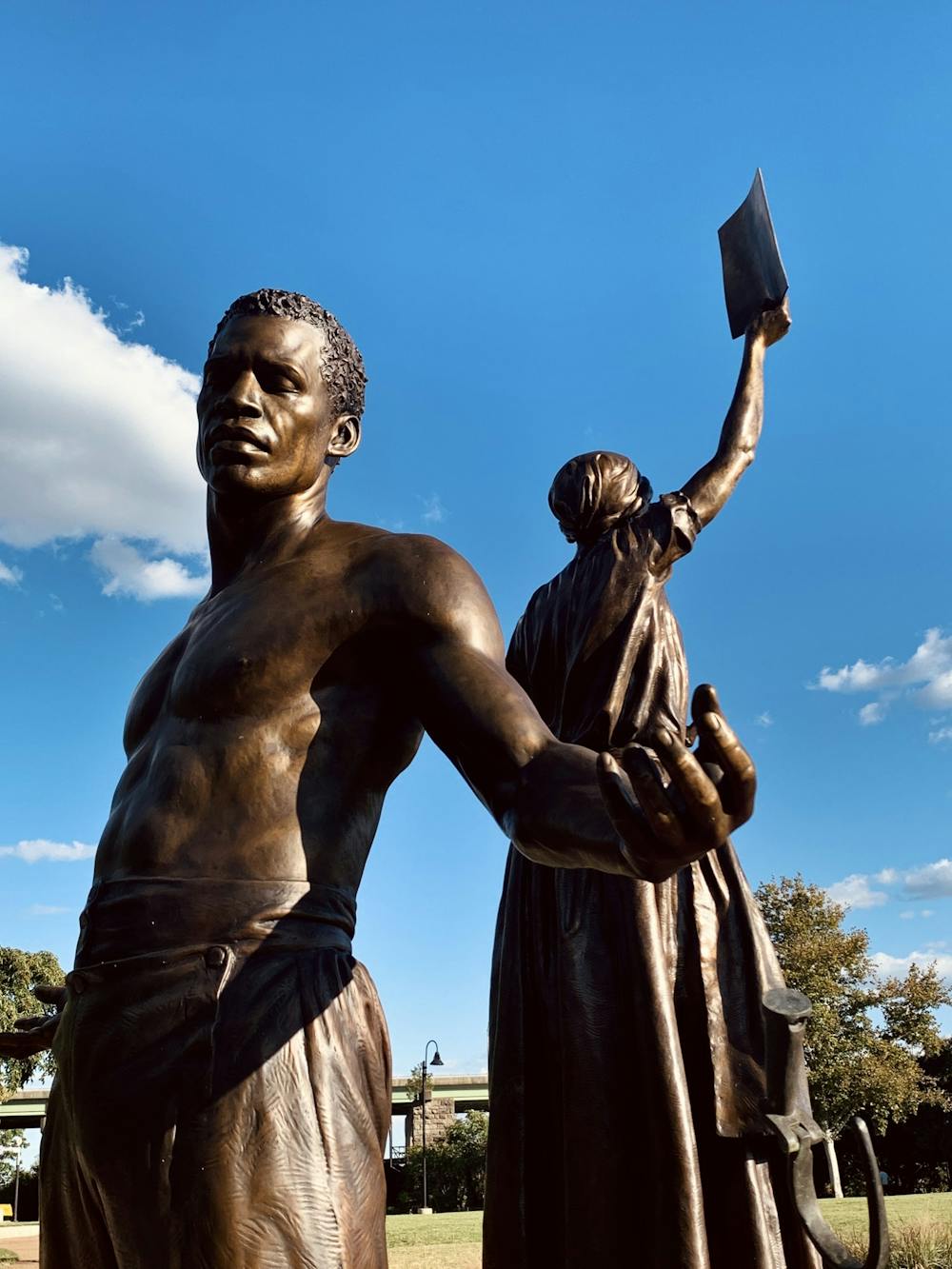

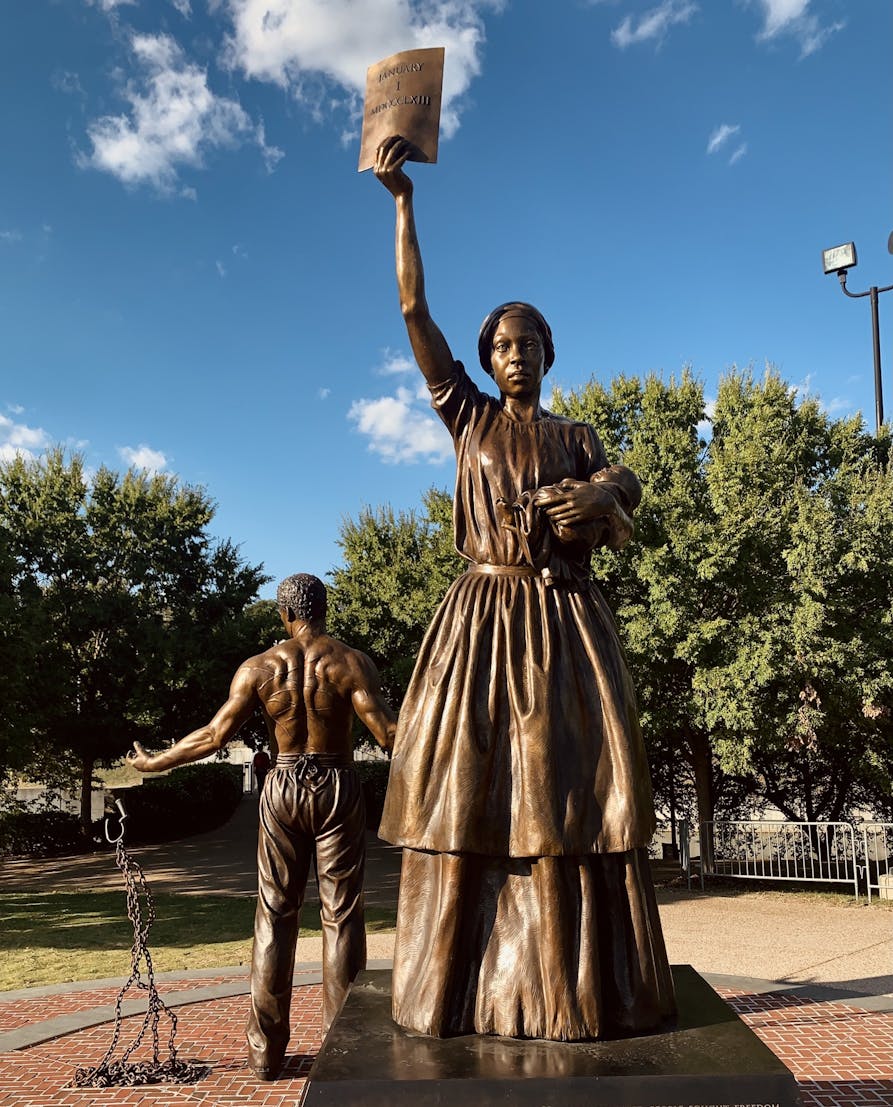

The first state-funded statues celebrating emancipation in the United States were unveiled on Sept. 22 at Brown's Island, a public park along the James River in downtown Richmond.

The statues feature a man, woman and infant newly freed from slavery. The monument also includes the names and biographies of 10 Black Virginians who were pivotal in the movement for emancipation -- five of whom fought against slavery in the time leading up to emancipation and five who fought for equality from 1866 to 1970.

Artist Thomas Jay Warren constructed the project, which was orchestrated by the Virginia Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission led by state Sen. Jennifer McClellan, the commission’s chair.

The unveiling ceremony included statements from Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney and Gov. Ralph Northam, both of whom emphasized the importance of making Richmond more inclusive.

“The hands of the enslaved built this city," Stoney said. "We were once the capital of the confederacy, and the capital of the lost cause. Well, no longer is that Richmond.”

In an interview with The Collegian, McClellan said the unveiling had been “almost perfect,” citing the rain that had fallen in the moments before the unveiling that, to her, did not dampen spirits whatsoever.

“When we pulled the curtain back, I just wept,” McClellan said. “It evokes all of the emotions and thoughts that I'd hoped it would when I first saw the model. To see the audience have the same reaction was just like, we're finally telling the rest of the story.”

A woman holding a baby and a pamphlet with a Jan. 1, 1863 date -- the day President Lincoln signed the emancipation proclamation -- stand alongside a man who appears to be breaking free from the chains of slavery.

The unveiling was supposed to occur in 2019 as a part of the 400th anniversary of 1619, the year the first African slaves entered Virginia, but was pushed back as a result of COVID-19 complications. However, after a year of reckoning with racial inequality following the death of George Floyd in May 2020, many people thought the timing was perfect.

“This was ordained to happen at the time it did as a moment of healing,” City Councilmember Andreas Addison said.

Councilmember Katherine Jordan, who attended the unveiling ceremony, contrasted the Brown's Island monument to the Confederate statues that used to line Monument Avenue -- in particular, the contested Robert E. Lee statue that was taken down only two weeks before the Emancipation and Freedom Monument went up.

Jordan described the new monument as an indicator of the shift in how the city is telling its stories, noting that for years the predominant statues in Richmond were of confederate “heroes,” whereas now there had been a change in the types of statues displayed.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

In 2017, a statue of Maggie Walker -- a Black woman who was the first woman to found a bank in the U.S. -- was placed on West Broad Street, and there are current plans to build an African American memorial park in Shockoe Bottom.

These statues -- along with the statues to come -- lay close to the ground, conveying the opposite of what Councilmember Addison described as “apotheosis,” or the state of being deified. He explained how 61-foot-tall statues, like that of Robert E Lee’s, are made to be divine, whereas statues that represent thematic ideas are made to be relatable.

“There’s a need for [a monument] to be approachable,” Addison said. “It doesn’t need to be high, it needs to be close.”

When asked about their view on memorials in general, both Addison and Jordan expressed some reservations.

Jordan explained how the judgment of people can shift over time, so a safer method would be to venerate ideas rather than people. The Emancipation monument and other monuments celebrating Black freedom from oppression and slavery exemplify this concept, she said.

The shift allows for a new wave of monuments that tell a different story, a story that McClellan says personally affects her as well as other Black Americans.

“Public history and monuments are all about who's telling the narrative,” McClellan said. “For so long African Americans’ didn't see their history displayed in public places. Now we do.”

Contact City & State writer Eliana Neill at eliana.neill@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now